A Canadian's First Nav in Australia

YRLL Number 1 or 2?

For the vast majority of student pilots, the first nav is a relatively short affair over territory at least somewhat familiar to the student, and certainly well known to the instructor. The opportunity for getting truly lost is therefore relatively low. However, sometimes a first nav is not so short or so predictable.

I came to flying later in life, making my first solo flight in Canada in a C-172 in January 2002 in my 51st year. Then, without worrying about the details of the why’s and how’s of my next stage of training, three weeks later in February 2002 I was taking off from Archerfield Aerodrome in a C172 RG on my very first nav. It was to be the first of many to come as I was embarking on an Australian cross-country tour, with my 21-year-old instructor, whom I will refer to as M.

And what nav training did I have to date? I had ground school and a back-seat ride on another student’s first nav – but that was it. Yet here I was, setting takeoff power as departed for a planned 5-hour day; YBAF to YHBA and finally to YRLL (Rolleston). As readers of Slipstream know well, the first half of that route can be a fairly hectic so I was going to be a busy boy. The confidence that I may have felt was mostly due to adrenaline and to an unwavering trust in my young instructor M. He was Australian after all and I assumed he knew the area like the back of his hand.

Suffice it to say that the first hours were challenging. The cockpit conversation went something like this:

M: “OK Clare, it’s time to get an updated QNH from Brisbane Central”.

Me: “Sure thing M, what’s a QNH again and can you confirm the frequency?”

M: “Clare, you need to do a CLEARO again or you’ll get behind the plane.”

Me: “Right M, I’m on it. What does the “C” stand for again?”

M: “Clare, we’re going to be taking a new heading soon. Get ready for your HAT check.”

Me: “OK M. Tell me again, is “H” for Heading or for Height? Ah yes, Heading.

Me: “M, what did the tower say? I was busy setting the new heading?”

Me: “M, did he want me to do that right now?”

Somehow, through patience and perseverance, we found ourselves descending into Hervey Bay without having disrupted the coastal airspace too much. I felt tired and was ready to call it a day. Unfortunately, YHBA was only our refueling stop and we still had well over two hours to go and we had to land this thing first.

Me (fatigued): “M, I can’t find the windsock. Oh yeah, there it is.

Me: Yes, I think we’re on the active side.

Me: What was the proper radio call again? I just wanted to say ‘Look out I’m coming in!’, but I knew that wasn’t acceptable.

Fortunately we did land without mishap, refueled and were back in the air heading to Rolleston, but much too quickly for me given my mental fatigue. To my relief the next leg was had much less radio work because of the reduced traffic and not ATC. I now found the biggest challenge was to stay on track. We did have basic GPS in the plane but it was turned off because this was to be a pilotage / dead-reckoning training nav.

I quickly learned that the Outback offers few fixed ground references, unlike my home turf in Canada. The cockpit conversation now tended to be focused on me trying to determine where we were!

Me: “M, why isn’t that road on my map? It looks like it should be.”

Me: “Do I really need three points to confirm a fixed ground reference? I have two!”

Me: “I am trying to hold my heading and altitude!

Me: Yes, I think I know where we are, I just need a decent ground reference to confirm!”

We were now well over 4 hours into our flying day. I was in an unfamiliar plane, dealing with retractable gear and a CS prop for the first time, with a new instructor and in strange country. But in spite of all the challenges we found ourselves approaching the Dawson Highway and thankfully Rolleston was now just a few minutes away. We were both ready and looking forward to getting back on the ground.

As we approached the highway from the south, M asked me if Rolleston was to our right or to the left. I was so tired I wasn’t sure which gauge I should be looking at to answer the question. Nevertheless, I had a quick look at the map and told him it’s to our left. But M disagreed, and proceeded to show me why he knew it was to our right. At this stage I was not even going to contemplate disagreement. He had more flying experience, familiarity with the terrain and the CPL. So off we went to the right and soon found ourselves over a collection of buildings.

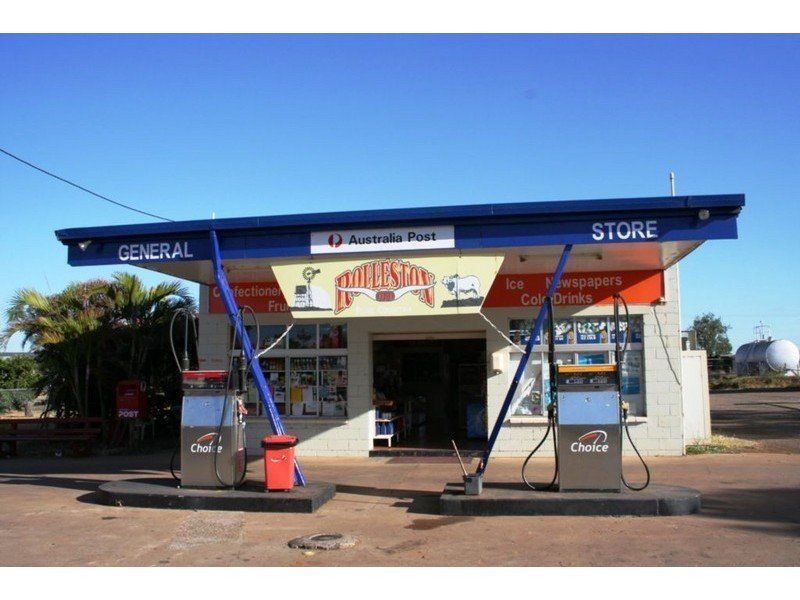

As we circled M confidently showed that we had the requisite three ground references points to confirm that yes, this was indeed Rolleston. We therefore landed on the dirt strip; no terminal building, no one in sight, and some houses a short walking distance away. But I didn’t expect much because Rolleston was a very small town. I felt the heat and was looking forward to getting into town and having a pint.

We took a few photos and prepared to walk into town, as it looked like nobody was coming to fetch us. At the time I didn’t know that was the norm, walking into town, at these more remote strips. However, a few minutes later, a white UTE unexpectedly came out from behind a knoll on the other side of the strip and headed for us.

Great! Someone to help us find food and a place to stay! There were two people in the vehicle and they both hopped out as soon as they stopped. They seemed friendly enough but instead of welcoming us, we were greeted with a warm, but somewhat reserved “What can I do for you mate?”.

M, always cheerful, explained how we were on tour, had just arrived in town, were looking for a room and a meal at the pub and could they give us some directions. The driver’s response was a bit shocking; “This ain’t Rolleston mate. You’ve landed at Planet Downs cattle station. Rolleston is about 30 kilometers west of here. Just follow the Dawson Highway and you can’t miss it.”

My first thought: I WAS RIGHT! We should have gone LEFT! Back in the plane, we flew a last unplanned leg, and finally reached the “real” Rolleston, hereafter known to M and I as Rolleston #2. He swore me to secrecy, not wanting to be the butt of a whole new generation of nav jokes back at the aero club.

Morals of the story:

1. The pilot with the greater number of hours is not always right.

2. GPS is a really good thing.

3. YBAF/YHBA/YRLL is not a good first nav.

Since that first nav in 2002 I have been lucky enough log many, many more hours in the Outback and love flying in Australia. And some day I think I’ll go back to Rolleston. I may even opt to land at Rolleston #1 for fun. And may you always land at the correct Rolleston on your first try!

Clare McEwan